Weak sun offsets global warming in Europe and US – study

Weak sun offsets global warming in Europe and US – study

Regional impact of a weaker solar cycle likely to be larger than global effect, with only minimal impact on worldwide temperature rises caused by climate change

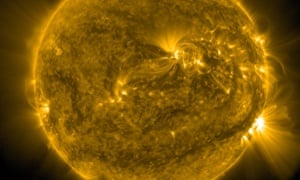

In the 17th and 18th centuries a grand solar minimum caused the River Thames to freeze over, but global warming is expected to raise temperatures too high for it have much effect in future. Photograph: Solar Dynamics Observator/NASA

Global warming in northern Europe and the eastern US could be partially offset in future winters because of the sun entering a weaker cycle similar to the one which enabled frost fairs to take place on the river Thames in the 17th and 18th century, according to new research.

However, the study said any potential weakening in solar activity would have only a small effect on temperature rises at a worldwide level, delaying the warming caused by emissions from cars, factories and power plants by around two years.

The sun has been in a period of high activity for the past few decades. But scientists believe there is now as much as a 20% chance of a weaker period of activity, known as a grand solar minimum, occurring in the next 40 years.

“Even if you do go into Maunder minimum conditions it’s not going to combat global warming, the sun’s not going to save us,” said lead author Sarah Ineson at the Met Office. The Maunder minimum is the name for the sun’s weak period during 1645-1715, when the Thames froze solidly enough for eyewitnesses to report horse-driven carriages crossing it.

Climate change means such sights in the second half of the century would not occur, since the sun’s cooling effect would only reduce manmade temperature rises in northern Europe and the eastern US by 0.4-0.8C. Such offsetting was not a “large signal”, Ineson said, although the study found there would be more frosty days in those regions than there would be without the weaker solar activity.

solar graphNorthern Europe and the eastern US would experience a much stronger cooling effect from a weaker period of the sun’s activity than other areas because less ultraviolet solar energy at the top of the stratosphere would cause a chain reaction which would affect the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). The NAO is a climate phenomenon which plays a key role in influencing winter weather on both sides of the Atlantic.

Another consequence of a changing NAO would be to make storms more southerly, bringing more rainfall to southern Europe and slightly lessening the drying trend the region is set to experience because of climate change. However, the effect is expected to be relatively small.

Globally, a grand solar minimum would reduce temperatures by just 0.1C between 2050 and 2099. Manmade climate change, by contrast, is expected to bring temperature rises of up to 6.6C in the same period if drastic action is not taken to cut carbon emissions.

Such a high level of warming would bring grave consequences as seas rise, drought threatens water supplies and food production suffers, scientists have warned previously.

“This research shows that the regional impacts of a grand solar minimum are likely to be larger than the global effect, but it’s still nowhere near big enough to override the expected global warming trend due to man-made change,” said Ineson.

Asked if the findings of her study gave European and US political leaders an excuse for weaker action on cutting emissions, Ineson said the reaction should be exactly the opposite, as it did not change the bigger picture on climate change.

The paper, Regional Climate Impacts of a Possible Future Grand Solar Minimum, is by a UK and US team based at Cambridge, Oxford and Reading universities, as well as the Met Office and the University of Colorado in Boulder, and published in the journal Nature Communications.

No comments